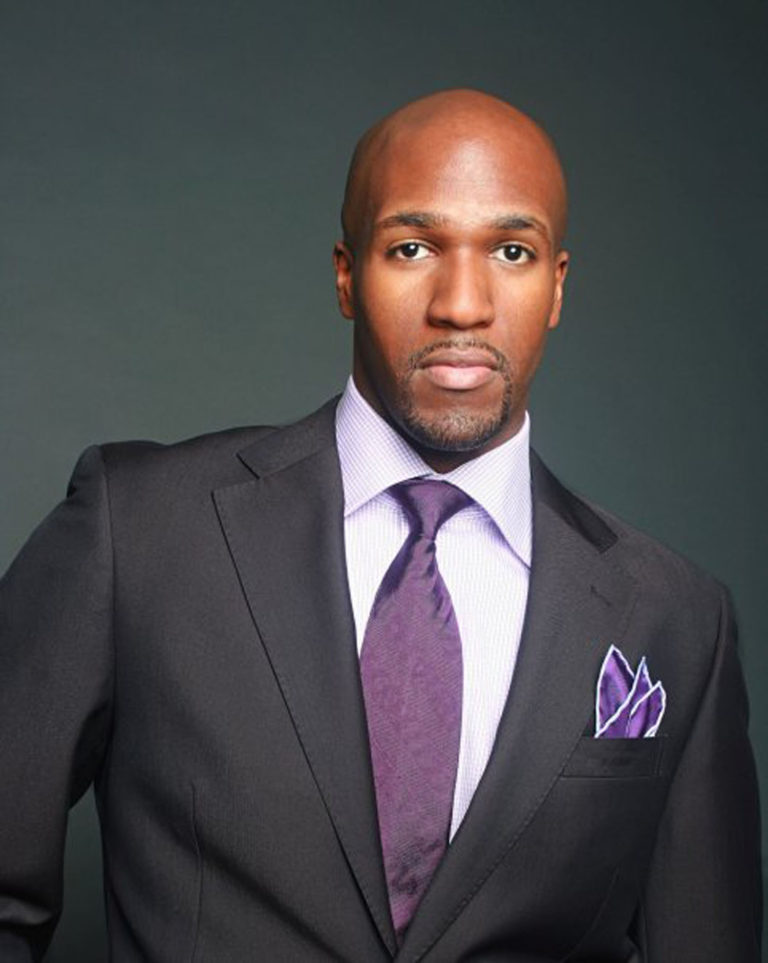

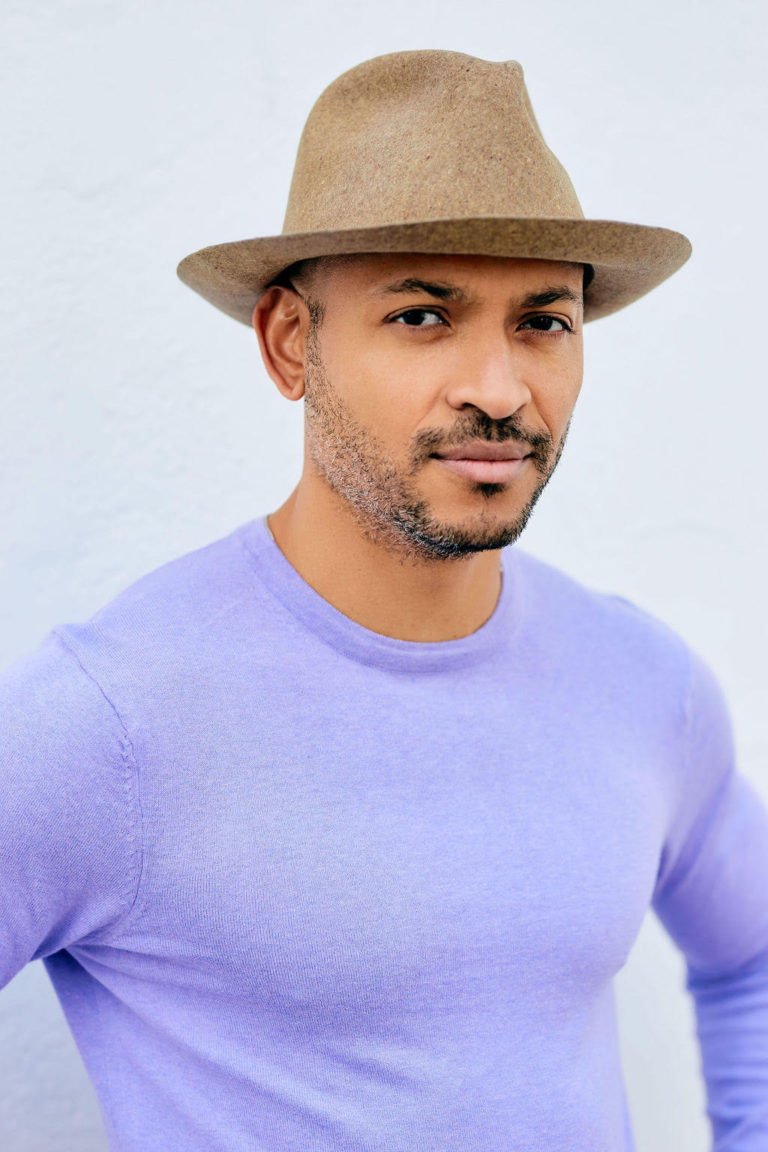

Marsha Thompson on artistry, advocacy

and activism in America

“Why aren’t our arts organizations ahead of the curve on this?” This was American soprano Julia Bullock’s passionate question during a virtual panel discussion on racial disparity and inequality—particularly as they pertain to Black Americans in classical music and opera—presented by LA Opera on Facebook Live last summer. It’s a simple question on the surface. But in essence, it’s loaded with implication. Historically and culturally, artistic communities and creative circles have often been at the center of the zeitgeist, pushing social perceptions toward progressive ideas that champion inclusivity, innovation, and understanding. The sad reality is that the seemingly exclusive, esoteric world of opera and classical music is hardly removed from the path of sweeping racial acrimony poisoning the nation at present. It is not, by and large, identifiable by gross, blatant offenses. Instead, it is subliminal, systemic, and subtle, made manifest through microaggressions and the intimate denials of our individual senses of self and agency. A glaring example of this dissonance can be found in Marsha Thompson’s story.

Texas-born and bayou-bred, Thompson is no stranger to the effects of micro-and macro-aggressions and implicit bias, and she has openly taken to social media to confront them.

“Artists throughout history have always been active in the social movements of their time,” says Thompson. The list of musical contributions in this category is quite literally endless, and ranges from Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro, seething with class conflict, to Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way,” championing self-expression and supporting LGBTQ+ rights.

So when Thompson was confronted by a major patron for her outspoken, politically charged online presence, it was disconcerting to be told that she should “be more neutral and just focus on making music.”

This concept is certainly not new. I’m sure we all remember when in 2018, conservative Fox News host Laura Ingraham unleashed a bitter, racially-tinged rant toward Lebron James and Kevin Durant after they spoke openly about their experiences with the ever-growing racial tensions in America at the time. They openly disapproved of then-president Trump’s tone-deaf, often incendiary political rhetoric. Ingraham’s rebuttal was a chilling “shut up and dribble.” The direct, and frankly dismaying, correlation between that nationally regarded exchange and Thompson’s personal one leaves a litany of questions and fears as it pertains to the roles and rights of Black celebrities in America. We here, as Thompson puts it, are so quick to pick and choose when people should and should not speak up and speak out.

“The real issue,” she says, “is that there is a contingency of people in the United States of America who do not want Black people to say anything, because they want you to sit back and wait until they are good and ready to give you a piece of justice, equality, and equity.”

But how has this warped view of roles and responsibility been able to proliferate so thoroughly within a society in which Black individuals actively claim major successes and achievements?

Thompson, for example, is renowned by numerous critics for her brilliant artistry. Her operatic Abigaille has been heralded as “exquisite,” and her Sieglinde “thrilling.” These roles, as we know, are no small feats, to be sure; and her list of accomplishments and accolades stretches to include Violetta, Aida, Bess, and many others, with noteworthy houses across the globe that include New York City Opera, Teatro Municipal de São Paulo, and Opera Carolina. Like James in basketball, she has proven herself a force in her genre, and yet she is still somehow subject to the swift debasement of her person due directly to the color of her skin. “It is acceptable for White America to observe Black suffering and pain,” says Thompson. “It is harder for some people to accept Black success and gain.” One of Thompson’s most notable roles was as Harriet Tubman in Nkeiru Okoye’s Harriet Tubman: When I Crossed That Line to Freedom at American Opera Projects in New York. Thompson would “transform,” as she puts it, in order to embody the depth and dimension of a woman whom she calls an American hero (and I am certainly inclined to agree with that designation). The creative process by which Thompson adorned this character certainly pulled on her own life experiences as a Black woman in America, and the portrayal she provided earned her high praises from mixed audiences.

It is this cognitive dissonance that I feel requires a working approach. Our society praises the concepts of radicalism, activism, perseverance, and individualism, when they are packaged in stage makeup and costumes and framed within a historical narrative. But then we denounce the same people who embody these tenets in their waking lives. According to Thompson, this false dichotomy is an immediate result of a deeply ingrained racist ideology that we deal with in this country. The concept of “shut up and sing” is an evocation of the time of slavery, when Black bodies were expected to perform as the soul was diminished.

“Black people could not have any self-esteem,” says Thompson. Thus, “ Black people do not have the privilege or the liberty to be ‘neutral’.”

So, the call to action? It’s very simple. “People [artists] should do what they are moved to do … we have to continue to encourage each other.”

This seems rather reductionist. But in this particular lane of society, we as Black artists find ourselves at a unique intersection of privilege and responsibility. To be endowed with the blessings that afford the ability to pursue the rarefied, often inaccessible fields of art and music is a privilege that not all of us are afforded. At the same time, we inevitably must face the weight of our daily lives as they are permeated by the ever-present effects of racism and bias in this country. How we do so, Thompson says, is an individual choice.

But by living into the freedom of that choice, and consequently the truth of ourselves, we give weight to the power of agency and self-determination.

Yes, there are certainly specific, quantitative changes that can be made at the institutional level—from conservatories hiring more culturally sensitive instructors, to arts organizations restructuring on an administrative level to include more Black board members, general directors, casting directors, and others.

However, there is also work to be done on the subconscious level in order to make it all sustainable. “It’s important for our humanity to be seen,” says Thompson. “And, since the United States has participated in colonization, it’s important for this country to make space for Black excellence, because we’re here.”