The hyper-conservatism that dominates classical music culture provides the perfect environment for secrets to hide in plain sight. It is not just the institutions or the cultural leaders at the helm that are responsible. It is us. Ours was among the last sectors of society to be effectively permeated by the progressive #MeToo movement, perhaps because we’ve been resigned to exist in our bubble, separate from the goings-on of the world at large.

On March 9, 2021, conductor James Levine died of natural causes in Palm Springs, California. He was 77 years old.

The Strange Case of James Levine

Once one of the most lauded and highly paid conductors in the United States, the end of his career and the final years of his life were marked by controversy and conspiracy. It is widely accepted that Levine’s singular tenure at the Metropolitan Opera, which covered four decades, shaped the country’s largest performing arts organization into the unassailable artistic organization we know it as today. Over 2,500 performances were led under his baton at the opera house, beginning in 1971, before allegations of child sexual abuse and sexual misconduct started to emerge in 2016. These led to his suspension in 2017 and formal dismissal in March 2018, following an internal investigation.

Levine was, by all accounts, a child prodigy, debuting with the Cincinnati Symphony at the age of 10 as the soloist in Mendelssohn’s Piano Concerto No. 1. He would go on to debut at the Met at 29, leading a production of Puccini’s Tosca before being named music director there five years later. The 10-time Grammy award-winner also served as music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s Ravinia Festival from 1973 to 1993, and of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 2004 to 2011. As chief conductor of the Munich Philharmonic, Levine led the orchestra from 1999 to 2004. He was also a frequent guest conductor for some of the world’s most elite orchestras.

His wide-spreading appeal even extended into popular culture, with features on PBS’s American Masters, Disney’s acclaimed Fantasia 2000, and a New York Times magazine cover in 1983. It is scarcely a surprise that Levine was commonly regarded as the greatest conductor in America since Leonard Bernstein, known for his ability to empower the orchestra to “function within the conception [of the score] without having to check with the middleman.

“How much do you have to give? How good do you have to be? When I go out, to the theater, to a restaurant, all I get from people I meet is wonderful feedback about what the work I do means to them. That’s what matters.”

This was conductor Levine in a 1998 interview with New York Times arts critic Anthony Tommasini. Two decades later, his words resonate with disturbingly eerie implications. At the time, Levine was responding to growing controversies surrounding his acceptance of the title of music director of the Munich Philharmonic—namely, the leaking of his lofty salary in a recession-gripped Germany, where arts institutions were grappling with sizable budget cuts. The German tabloids took aim at Levine’s fiercely guarded private life, promulgating innuendo into his sexuality and fringe proclivities. Meanwhile, rumors of his sexual misconduct, harassment, and abuse had been percolating within opera and classical music circles since the 1980s.

In 1987, the Times published an article wherein Levine first addressed the rumors publicly, saying, “… people can’t believe the real story, that I’m too good to be true.”

Johanna Fiedler, chief press liaison for the Met from 1975 to 1989, later wrote on the subject. “Perhaps the stories arose because Levine—then, as now—exudes friendliness and warmth, yet has an intense desire for personal privacy.” I believe it is because of our inclination toward hero-worship of some of our biggest stars that such minimizing rationale as Fiedler’s has sufficed as an acceptable answer to the mounting accusations. The rumors have been relegated to industry gossip, forgoing any real investigation.

Justin Cohen, a Juilliard graduate and former professional trumpeter, vividly recalls mentioning to a New York City Opera vocal coach around 1990 a story about Levine having been caught molesting a young male in New York’s Central Park. Cohen says, “She responded with vehemence that it was not rumor, and that a staff member at the Met had confirmed it as widely known fact.” Obviously, many people knew at the time about Levine’s behavior. Yet he seemingly experienced no professional or legal consequences, his actions an open secret.

In total, nine men went on record publicly accusing Levine of abuse, with allegations spanning from the 1960s to the 1990s. At that time, many of the victims were teenagers or in their early twenties, vulnerable artists who were in the early stages of their careers and under Levine’s tutelage and mentorship. Upon his dismissal in 2018, the Met released a statement saying their investigation had “uncovered credible evidence that Mr. Levine engaged in sexually abusive and harassing conduct.”

Levine sued the Met for breach of contract and defamation and was countersued by the organization for violating his duties and harming the reputation of the institution. The legal battle ended with a quiet settlement in 2019, Levine emerging with $3.5 million. He was never charged.

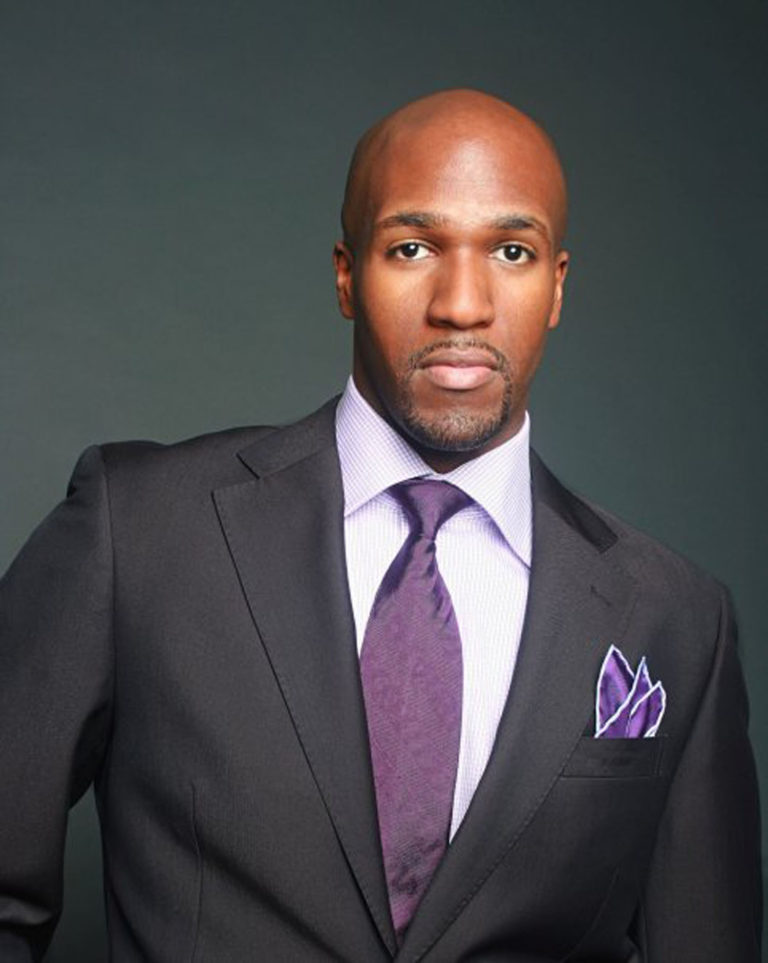

Levine’s knotted legacy finds its roots not only in the success of major arts organizations, like the Met and the BSO, but also in the career successes of countless world-renowned vocalists for whom his influence opened many doors. These artists include James Morris, Aprile Millo, Kathleen Battle, and Morris Robinson.

“This dude was a genius of unparalleled proportions,” said Robinson in a Zoom interview with me. “If it weren’t for him having that foresight and taking a chance on me, we wouldn’t be having this conversation right now, because I just would’ve been one of those guys who just passed through and didn’t make it.”

Robinson, who didn’t begin singing until the age of 30, was quickly identified by Levine as a special talent worth nurturing, and rightly so. However, with the emergence of the allegations and mounting evidence against his mentor, Robinson was nevertheless heartbroken by the revelations.

“Because a lot of old scenarios were being unearthed around that time,” he said, “like Bill Cosby and Epstein, I thought, ‘Is this really happening?’ I was hurt, and I was shocked.”

In Robinson’s case, the relationship that was cultivated between himself and his mentor was one of rigorous artistic exploration and discovery, and the professionalism shared between the two never faltered.

Regarding the type of media coverage surrounding the mounting scandal against Levine, Robinson feels there’s a fundamental issue that many of us, frankly, tend to overlook.

“I think that a certain amount of responsibility comes with being a public figure,” he says. “When you achieve a certain status, all aspects of your private life become public knowledge, and I think that’s unfair for anyone and everyone involved.”

I appreciate this comment, not for Levine’s sake, but for that of his victims and the loved ones that survive him. When sensationalism and salacious journalism grip a story, especially one of such consequence, the collateral damage often ripples indiscriminately through the lives of every person involved, regardless of culpability or victimhood.

Opera and classical music’s hyper-conservative culture is changing, though, primarily as a response to the rapidly evolving zeitgeist of society and, more specifically, creative communities. Antiquated models of leadership and oversight are shifting to empower individuals not from the top-down, but from the bottom up.

In that vein, the deification of individuals, regardless of their profound contributions to their art, is reckless. As we’ve seen in the cases of Harvey Weinstein and Woody Allen, artistic barons must no longer be shielded by their celebrity or the institutions that protect them. As this new wave of oversight and accountability sweeps through the classical music community, we might reflect on how we, as individuals, can contribute to the progress.

To consistently champion the higher ideals of community over hero-worship is to actively protest the status quo. If enough of us within these circles were to do so, perhaps the space that allows for abuse to occur would shrink. Even more importantly, cancerous rumors would not simply spread through the community unchecked for decades.

Levine was once quoted as saying, “I was brought up to take responsibility for myself, to obey the natural laws of my personality and gifts.” Ideally, this type of hubris, when pitted against the pressures of our collective ethos, would not thrive, but whither and fade. Despite his enduring influence on the industry and the art itself, Levine was, after all, just a man—complicated, fallible, and finite.

As novelist Robert Louis Stevenson wrote, “… I learned to recognize the thorough and primitive duality of man; I saw that, of the two natures that contended in the field of my consciousness, even if I could rightly be said to be either, it was only because I was radically both.” —The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde