There are many subjects, articles, and books which incorporate the words “the art of” in their titles. There are The Art of Racing in the Rain, The Art of Self-Defense, The Art of Getting By, and of course, Julia Child’s classic, Mastering the Art of French Cooking (volumes 1 and 2). The use of the word “art” in this context suggests a certain level of mastery, though it’s probably no safer to judge a book by its title than by its cover. It is uncertain who first coined the phrase, “The Art of the Spiritual”—the great impresario W. Hazaiah Williams, or perhaps someone else. No matter who said it, the catchphrase has had only modest staying power. The notion of the spiritual as high art is a concept which we, here in America, still struggle to accept and acknowledge.

So-called Negro spirituals are the elocution of both Christian ideology and the hardships of slavery in song form. From their infancy, they served as the only unhampered means of self-expression available to the Negro. These folk songs, derived from the field holler, are more than recollections of biblical stories and dialect-laden verses set to music. The spiritual, in its simplest, monophonic form, is layered, nuanced, and meaningful, requiring sensitive, thoughtful interpretive prowess to deliver. In fact, so complex are these songs that they may be divided into four categories for further distinction: Sorrow Song, Signal Song, Testimonial, and Jubilee.

Sorrow Song

W.E.B. DuBois was the first on record to describe musical compositions that spoke of the suffering of enslaved Africans in America as Sorrow Songs. These songs are often slow and sustained, with a long-phrase melody that allowed the lyric poet to express the feelings of a people subjected to unjust treatment.

Signal Song

Signal Songs represent the most intricate of all the spirituals types. These songs were the secret code by which slaves were able to communicate, expressing their dissatisfaction with their present condition, cries for revolt and protest, and plans to escape from oppression.

Testimonial

Testimonial spirituals are what the name suggests: they are a recollection or account of a life-changing occurrence that transformed the life of the storyteller.

Jubilee

Jubilee spiritual texts essentially refer to the biblical year of Jubilee, with personal liberty and restoration of property being the cause for celebration.

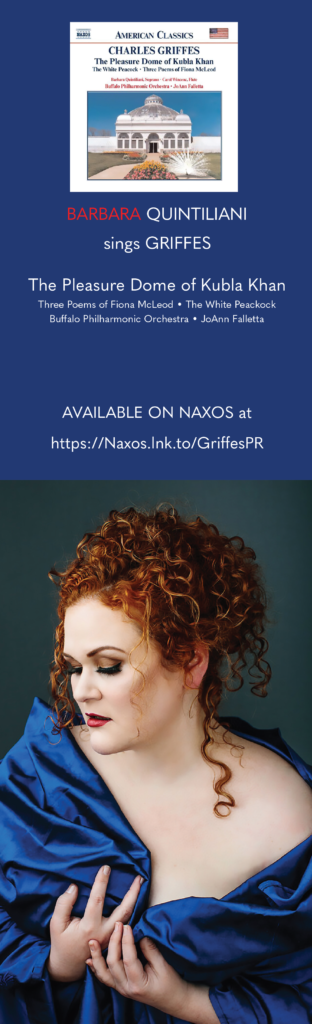

As the Negro’s educational opportunities increased, spirituals moved from the field and the outdoor camp meeting to the recital hall and concert stage. John W. Work, Harry T. Burleigh, and Robert Nathaniel Dett were instrumental in the push to give credence to the Negro spiritual as high art. Recitalists Marian Anderson, Roland Hayes, and Dorothy Maynor, the most prominent black classical singers of their day, toured with Work, Burleigh, and Dett arrangements in tow. Their performances of spirituals earned them praise all over the world. In later years, Leontyne Price, Betty Allen, Simon Estes, and other prominent black artists concertized with spirituals, often inserting them as footnotes to programs of classical western European fare by Brahms, Schubert, and Schumann. One major proponent of this genre—Negro spirituals—is the American opera singer Barbara Hendricks. Hers may be a bit of a forgotten name in the United States, as Europe has been her home since the late 1970s. But with several Negro spirituals discs in her vast discography and countless tours of spirituals concerts, Hendricks is a standout in the field as one who celebrates and champions their art unwaveringly.

“Down by the Riverside”

with Barbara Hendricks

Spirituals: The Music I speak, the words I sing.

Barbara Hendricks’ shimmering, crystalline voice has taken her to the great opera houses and concert stages of the world. Her soulful, stirring performances likely stem from the inspired, fiery singing she heard as a young girl growing up in the segregated south. An early influence was the great gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, who was widely praised for her rich, sonorous contralto voice. Hints of Jackson’s influence can be found in Hendricks’ nuanced portrayals of Mimi in Puccini’s La Bohème, and even in her recordings of Schubert, Brahms, and Fauré. These vocal affectations are best put to use in her captivating recordings and stage performances of Negro spirituals.

Born in 1948 in Stephens, Arkansas, to a C.M.E. minister, Ms. Hendricks’ earliest recollections of spirituals are the summer church revivals her father pastored, which “were the classroom that exposed [her] to the history of [her] people through the songs of the slaves.” When asked about her formative years, and the influential figures who cultivated her passion for spirituals, three names immediately spring forward: Wilbur Glenn, Arthur Porter, and Jennie Tourel. Hendricks’ first formal experiences with spirituals came after high school choir director, Wilbur Glenn, bent the rules to allow the twelve-year-old to join his choir “because he needed sopranos.” Hendricks was fully endorsed by her primary school teacher, who put Glenn onto the young soprano with the crystal-clear high C. Hendricks says, of those days in Wilbur Glenn’s choir, “the first time I heard this kind of concert singing of spirituals was with him.” After some time moving around between Memphis and Chattanooga because of her father’s work, her family landed in Little Rock, Arkansas, where she sang in the Horace Mann High School choir. It was directed by the jazz pianist Arthur Porter (known in music history as Art Porter, Sr.). “Both Mr. Porter and Mr. Glenn taught us that spirituals were important music, and it was important music for us to know and to sing well. Then later, when I went to Juilliard, my greatest influence was my teacher Jennie Tourel, who taught me to sing the words and speak the music.”

It is likely this approach to vocal literature that allows Hendricks to sing spirituals written in dialect with clarity of diction. Dialect remains a sore spot for many African Americans. The language of the uneducated African in America represents a foregone time in history that dredges up painful memories of oppression. Many prominent, highly educated arrangers used dialect in their works, including John Work, Harry T. Burleigh, Robert Nathaniel Dett, Edward Boatner, Hall Johnson, and Jester Hairston.

For Hendricks, “there is no need to be ashamed of that language.” She asks, “How many African languages did we have within that were destroyed within us, and we made do with no education, and we still managed somehow to learn and speak English without anyone teaching it to us? The dialect is a part of who we were. So, I always use the dialect when singing spirituals out of respect for the people who said those words.”

Even the name of the genre raises questions and calls for discussion. As labels changed from Negro to Colored, to Black to African American, so too has the name of the musical genre changed from Negro spiritual to African American spiritual. But for the soprano who “comes from a generation when labels were different … they are Negro spirituals.” Despite the triggers and defensiveness that dialect and the use of the word Negro bring up for the African American singing artist, performing recitals of spirituals abroad is still a draw. Hendricks says, “I could have gone my entire career just singing spirituals because they [Europeans] absolutely love them.” She has performed spirituals throughout her career, and has two highly praised spirituals discs to her credit. Those concert tours of spirituals inspired her first album, which was a collaboration with pianist Dmitri Alexeev. She recalls, “I was on tour giving a recital in Moscow, and during one of the breaks the pianist was sitting at the piano playing a little jazz.” The two tinkered around with some of the songs from Hendricks’ childhood and “decided to put together an entire program of spirituals.” She continues, “It’s so funny, people ask me all the time for the [sheet] music for that record, and I have to tell them that I don’t have it because we both just improvised that whole album. After I did that [record] I wanted to do another spirituals program, but I was looking to get back to this a cappella singing that so inspired me from my revivals in rural Arkansas.” As fate would have it, she would get the opportunity to perform her beloved a cappella spirituals in collaboration with one of the 20th century’s most innovative and prolific arrangers, Moses Hogan. She recalls being in a hotel room in Atlanta when a familiar sound came across the radio, and saying, “that’s it, that’s what I want.” She had her representatives call NPR to find out who the choir was, and was later put in touch with Moses Hogan. She and Hogan worked together, and decided on a program with which they later toured across Europe and beyond, ultimately recording a disc of spirituals called Give Me Jesus for EMI.

When speaking of these precious recordings, Hendricks’ recollections are nostalgic, heartwarming, and filled with full-throated chuckles that signal fond remembrances of her vast and varied career. It was, however, her enthusiasm for the gospel singer Mahalia Jackson that inspired a deeper look into the Negro spiritual, and how it has been used across other media, including television and film.

The Spiritual Beyond the Stage

Mahalia Jackson was a unique artist, given a worldwide platform that so many of her colleagues and contemporaries only dreamt of. She sang spirituals and gospel all over the world to great acclaim. However, it was her rendition of the spiritual “Soon I Will Be Done” (Trouble of the World), in the 1959 film Imitation of Life, that etched her into the annals of film history. Her rendition apparently moved the actors to tears during filming, including the movie’s star, Lana Turner.

Filmmakers use music in the same way opera and musical theater composers do—to create effects, underscore text, and move the drama forward. Name your favorite film, and there is likely a soundtrack that has played an important role in that film’s success. What many people may not realize is that Negro spirituals like “Trouble of the World” have been the unsung heroes of many television series and films across the decades. Here is a small selection of movies featuring spirituals that you can add to your movie night queue.

- HALLELUJAH

(1929) - THE GREEN PASTURES (1936)

- IMITATION OF LIFE

(1959) - LILIES OF THE FIELD

(1963) - SCHOOL DAZE

(1988) - RED HOOK SUMMER

(2012)