The fanciful world of Mozart’s classic opera The Magic Flute comes to life in a new film adaptation

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute, which originally premiered on stage in 1791 (with libretto by Mozart’s colleague, Emanuel Schikaneder), has undergone two film adaptations over the last half-century. Christopher Zwickler sees the potential for magic in a third iteration, one that is both a gateway into the world of modern opera and an updated take on Mozart’s work.

With the film in post-production, audiences can look forward to this modern magical tale in autumn/winter of 2022.

Zwickler, producer of the opera’s eponymous upcoming film, grew up an avid fan of The Magic Flute and dreamed of creating a contemporary screen adaptation. Director Ingmar Bergman’s 1975 version is more or less a filmed stage play, and indeed, stage performances have allowed for hundreds—if not thousands—of individual perspectives on the original. Another 2006 version, directed by Kenneth Branagh, takes place during World War I and was part of the 250th anniversary celebration of Mozart’s birthday.

Looking at the colorful world of The Magic Flute, Zwickler envisioned a film adaptation that would capture the accessibility of songs for the performers themselves, and the accessibility of the story for audiences to “jump into opera.” He elaborates, “It is a brand that is known all over the world. And even the [arias sung by] the Queen of the Night or Papageno, for example, can be sung by people all over the world. It has quite a broad appeal … so I thought it would be a great opportunity to tell it in a way that has never been told like this in a film before.”

Zwickler’s vision caught the attention of actor and director Florian Sigl during a happenstance meeting at a film festival in Berlin. Sigl studied classical music, and Zwickler had a musical background before getting into film. Combining their talents and backgrounds, the two set to work on developing their approach to tell the story for a younger, wider audience.

This approach includes a few key elements, one of them being the frame story. The audience is introduced to Mozart’s story line through 17-year-old protagonist Tim Walker, who gets a scholarship to attend a Mozart boarding school in the Austrian Alps. After traveling by train and arriving at the school, his excitement dissipates as he is faced with the competitive pressure—and an evil headmaster. Reckoning this reality with what he expected of the experience, he wanders the halls at night and ventures into the library. It is here that he discovers his copy of the book, The Magic Flute, fits perfectly in an empty space in a glockenspiel clock. Putting the book into place, he activates a portal mechanism, transporting him into the world of The Magic Flute as the protagonist of the opera, Prince Tamino.

This creates the levels of the story, with Tim entering this new world mostly at night. According to Zwickler, the coming-of-age story that happens within the boarding school is about 40% of the film, and the updated Magic Flute story line comprises the remaining 60%. Using Walker and this frame story literally and figuratively draws people, particular the targeted younger audience, into the operatic tale.

Sigl echoes Zwickler’s sentiments about the ways in which this third film adaptation intentionally differs from its predecessors. “Bergman made the conscious choice of keeping it as a stage play, whereas Kenneth Branagh mainly changed the setting of the story. Our approach is coming back to the original setting, but staged for a movie with fantastic locations.” Great care went into picking the right locations, in order to “enhance the escapism with a visual and musical experience that only the big screen and acoustic setup of cinema can ensure.”

Zwickler elaborates on the importance of setting to distinguish the layers of the story, and the necessity of creativity and resourcefulness when things do not go according to plan. Originally, Morocco and Bavaria were scouted as locales for the magical realm and the boarding school, respectively. However, Covid-19 made filming in Morocco virtually impossible, challenging them to come up with a financially feasible solution for constructing multiple worlds a bit closer to home. Working with a local film studio, the film’s art director, Christoph Kanter, devised a plan to use one large studio that, with careful planning, could be transformed into many different settings. One minute it is a bustling market, the next minute (or more realistically a few days later) a temple, then refashioned again into the palace of the Queen of the Night. When not in the studio, the production team was on location in Salzburg, shooting at places like Schloss Leopoldskron, where part of The Sound of Music was filmed. Bavaria makes for a stunning location aesthetically, and is an important nod to Mozart’s original, which premiered at the Theater auf der Wieden in Vienna.

In addition to filming on location, another example of the enhanced visual experience provided by film is the snake that chases Prince Tamino/Tim Walker when he first enters this alternate world. The snake is an incredible, life-like CGI effect created by Pixomondo, the company known for the dragons in Game of Thrones.

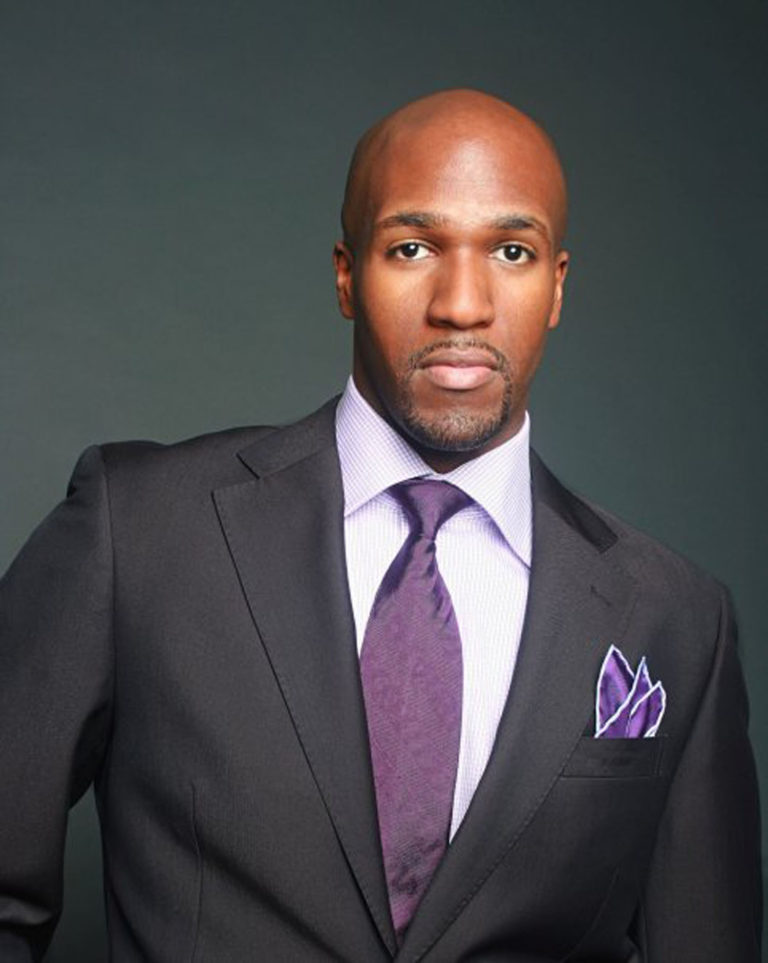

The final element to Zwickler and Sigl’s approach is the music. Even Mozart’s original utilized music in an innovative way through singspiel, or a mix of spoken dialogue and song. Sigl noted that the spoken dialogue and song breakdown in this film is roughly 50/50. “We carefully modernized the dialogues and transformed, where applicable, most of the recitatives into spoken dialogue. But it’s important to note that we did not change Mozart’s orchestral arrangement at all.” While Sigl and Zwickler did not change the arrangements, “the Mozarteum Orchestra Salzburg was recorded in 70 channel 3D sound,” adding to the musical experience. With another nod to Mozart’s original intent, Sigl and Zwickler adapted the singing style to each performing character—that is, “the younger the character, the less formalistic the singing style,” comments Sigl. “At the same time, we tried to reflect the evolution of theatrical singing and connect it to our medium [of] film. This allows us a broader dynamic range catering to the specific or emotional needs of each aria.” Cut to Morris Robinson, a former football player turned opera singer and the film’s Sarastro. From football to opera to film, Robinson calls it all by one name: performing. However, Robinson admits, “this allowed me to play a smaller, more intimate Sarastro … Because it is a film, I had to learn to adapt really quickly to small frame acting. I’m used to being commanding and utilizing my presence to assert authority. Film, however, works within a small space.” After Zwickler reached out to him on social media, Robinson was drawn in by the opportunity to reimagine a familiar role, but in a different context. “I was able to explore Sarastro the human, and this in and of itself was intriguing enough.”

Robinson makes very deliberate decisions regarding expansive roles—expansive roles for him personally, and for Black performers generally. This role allowed him to increase his range and blaze the trail for the next generation of opera singers, particularly those who look like him. “Anything I can do to lead the charge and show off our versatility as artists, musicians, and actors, I’m here for it … I hope this is just another example of our talent, versatility, and range such that other producers and directors look in this direction for Black talent. We are here.”

This sentiment also refers to opera singers as a talent pool. Robinson sees a wealth of opportunity for the opera world to participate in film. “In the opera world, we are professional actors and actresses already. Why not look at our marketplace, our discipline, our art when outsourcing talent in the world of film?”

Casting for the film in general was a pleasant surprise. For one, Robinson will be featured in both the English and German versions of the movie because he has sung Sarastro’s role more times in German than in English, a fun fact that was originally unknown to Zwickler and Sigl.

And there were concerns about casting such a young protagonist. Prince Tamino is often portrayed by a trained opera singer in his 30s, 40s, even 50s. Enter “stage” right Jack Wolfe, cast as Tim Walker/Prince Tamino. Zwickler is excited about the “sensitive way” in which Wolfe approaches the arias, adding “a unique ingredient to a piece like this.”

And there were concerns about casting such a young protagonist. Prince Tamino is often portrayed by a trained opera singer in his 30s, 40s, even 50s. Enter “stage” right Jack Wolfe, cast as Tim Walker/Prince Tamino. Zwickler is excited about the “sensitive way” in which Wolfe approaches the arias, adding “a unique ingredient to a piece like this.”

The film brings together actors who can sing and opera singers who, as Robinson noted, are already trained actors. Robinson as Sarastro and French soprano Sabine Devieilhe as the Queen of the Night bring their operatic expertise. In addition to Jack Wolfe as Tim Walker/Prince Tamino, Welsh actor Iwan Rheon—again drawing from Game of Thrones talent—joins the cast with his singer/songwriter chops. This confluence of different talents and worlds is especially exciting because it wasn’t a sure thing that artists in the classical sphere would be so keen on this fresh take. The key to the successful fusion: each performer brings his or her authentic self to the project.

And in this way, in convening and showcasing such a wide range of performing arts, Sigl is committed to “showing a broad audience how timelessly beautiful classical music can be, and break[ing] up boundaries that still seem to exist.”